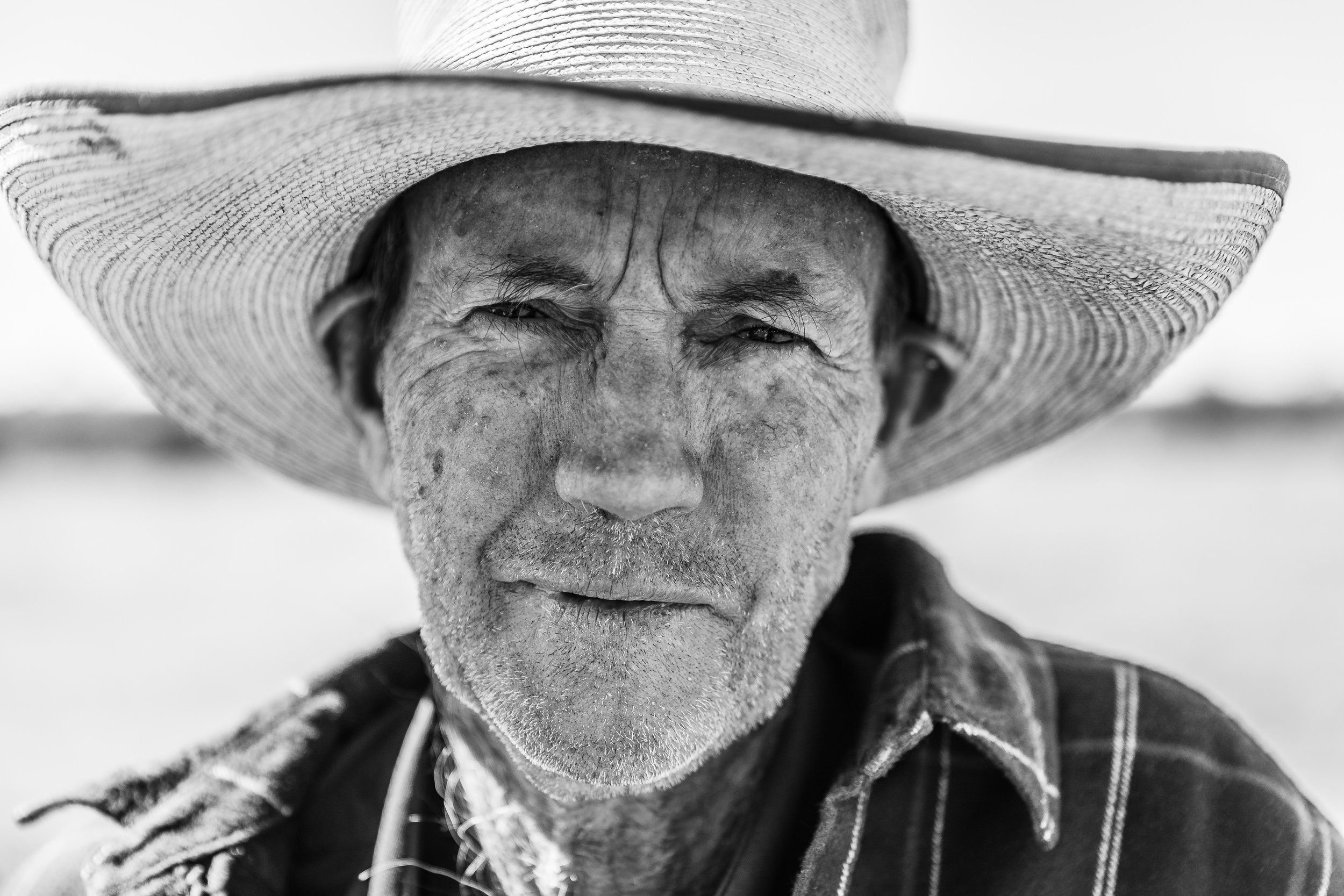

Steve Hawe: Fencer, Dreamer

Steve Hawe at Nehla Downs, near Isisford, Queensland.

Steve Hawe has spent his 50-year career working hard with his hands - but inside his creativity awakened.Words: Jessica Howard. Photography: Lisa Alexander and Håkan Ludwigson.It's been raining when I catch Steve Hawe on the phone at his base, 60 kilometres west of Isisford in central western Queensland. He's contract fencing and only rests when the weather forces him to. "We're building about four different types of fences, including a couple of k's of dog fences," he says. "Later in the year, we'll be back to the four-barb stuff."

Steve is 65 now, and has done hard physical work since he started fruit picking at 15. "My parents were school teachers in New South Wales and we shifted around a lot, with really nowhere to call home," he says. "After I fruit picked, I headed up to the Territory, and I never came back for 11 years."

It was 1973. Steve cut his hair, decked himself out in ringers gear and embraced station life, all for $28 a week. "It was terrific," he says. "We were just out bush. I was learning about horsemanship and cattle. The biggest thing was learning how to throw wild cattle from horseback."

In the years that followed, Steve moved through the jobs and up the ranks ("someone would always offer you a new job"). He slept in a swag on the ground in stock camps without toilets or running water, and worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Aboriginal stockmen and city boys on a gap year. "Everyone had boils," he remembers. "I think it was lack of vegetables. Some of us had shocking carbunkles." Despite his spartan life, or perhaps because of it, Steve's creativity began to awaken. Words bounced around his mind and he poured himself into leatherwork, making whips and hobbles for the camp in the wet season.

In 1985, he landed the Head Stockman job at Bradshaw Station. It was a huge responsibility for the then 28-year-old, who by this point had added a mattress to his swag for his ringer girlfriend Vicki. Within months, she was pregnant. And then, he met photographer Håkan Ludwigson.

"We were walking 1100 mickeys and clean-skin heifers back to Bradshaw when I got the radio call," he says. "There were no paddocks and we had quite a lot of weak cattle on the tail that we really had to look after, so it was one of the more difficult jobs I can remember."

Steve was reluctant to add to the stress by allowing a Swedish crew to traipse through his camp among skittish cattle that had to be night-watched because there were no yards. Tension is scrawled across his face in Håkan's portraits - his bloodshot eyes betraying the nights spent guarding cattle.

"Stockmen have a lot of time to think in those situations, when you're walking cattle and watching cattle," he says. "You think to yourself: is your life getting away? Are you going to do this the rest of your life?

"That time in the stock camp when Håkan was there,

I was sort of looking for what's next."

So after the 1985 mustering season, he ventured south with Vicki and baby Robert. He wanted to own country, but knew he never would in the Top End - dominated as it is with large lease-hold stations.

Steve Hawe in 1985 captured by Swedish photographer Håkan Ludwigson.

Steve bought and sold a couple of smaller blocks over the next 20 years, got a new wife Denise, inherited three children and made another of his own, Kate. Finally, he bought the property he'd always wanted: Spring Plains - 42,000 acres of marginal country near Longreach."We really took a hell of a risk" he sighs. It was chewed out from overstocking, but Steve and Denise didn't mind, because it was all theirs (... and the banks). "That's when we really ramped up the contract fencing," he says. "So we didn't have to look at the sky to see if we'd survive."

There were (more) hard years - they fell deep into drought and Denise had a stroke - all the while, Steve's creative flame grew stronger. When his daughter handed him an old laptop, the words fell out of him: "For me, it was a way of getting off the world for a while during all our problems." His short stories won some awards - and he started crafting a novel. "All the people I've worked with over the years - they all come out in your characters."

As Denise grappled with recovery, she and Steve built a flock of dorper sheep to sell for meat to local butchers. Denise grew interested in working dogs, while Steve sank star pickets and unravelled kilometres of feral netting. They bought another block in Warwick, south east Queensland, "closer to where things were happening," where Denise could start a working dog school.

Now, change is afoot again for Steve in a life "ruled by no rules". He's just finalised the sale of Spring Plains, and plans to give up contract fencing at the end of the year: "I worked hard all my life and I'm tired.

"I read 'A Fortunate Life' by Albert Facey and I feel like I'm the same. I've worked really hard, but I feel like I've had a terrifically fortunate life.

"You certainly make your own luck, there's no doubt about it."

He wants to make time for writing, or perhaps become a teacher ("but I'm worried I'm too old"), and nurture the thoughtful side of himself born during long periods of solitude. "Someone asked me: you've sold Spring Plains, are you sad? I said: no, I'm ready for the next step, whatever it is."

Steve Hawe's book 'My Time of Eagles' is out now via Boolarong Press. Find out more at stevehawe.com

Steve is looking forward to the next chapter of his life, as he prepares to retire from contract fencing.